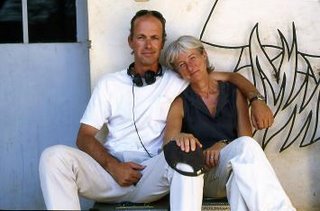

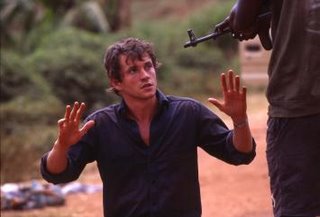

Director's thoughts.Michael Caton-Jones on Shooting Dogs.It was the sound that got me. Some sounds are so visceral they transcend words. You feel them in your stomach. We had been standing, my crew and I, as the sun dappled through the trees on to red-dirt African schoolyard, about to make our first shot of the day. We all stopped working as a minibus bounced noisily out the gates. It was full of teenage schoolgirls screeching and yelling. In any other place that would have been unremarkable, the heady chemical mixture of age and innocence on a school outing.

But here, in Rwanda, it was not a benign noise. The screams were not ones of youthful delight. This sound was terror. The hysterical reliving of personal horrors. A half-dozen private hells being given human voice. And I had been partially responsible.

The previous evening we had filmed a group of extras parading noisily as the notorious, machete-wielding Interahamwe militia. We were always careful to keep these scenes hidden from the public for fear of causing undue distress. We had made the shots, packed up and gone ho

me. However, a nearby dormitory of students heard the chanting and whistling and it had triggered a series of panicked flashbacks among them. Twelve hours later they were still in trauma, and the minibus was taking them to be hospitalised. It was then that I really understood the seriousness and responsibility of what I was doing.

I was in Rwanda to film Shooting Dogs, an account of what happened at the Ecole Technique Officielle (ETO) during the first five days of what became known as the Rwandan genocide.

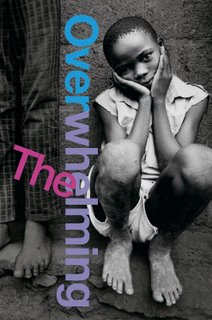

When you tell people you were in Rwanda, you often see a look of hazy recognition in their eyes. They know something horrific occurred there, but the details tend to be vague. For many, the word Rwanda has become a simplistic symbol for Darkest Africa, home of the bestial and barbaric. In representing a specifically Third World madness, it neatly fuses lazy racial preconceptions with a frighteningly widespread First World ignorance. It was something "they" did to each other, over "there".

Of course, it didn't stop those looks of hazy recognition from taking on a vicarious glint. So, what was it like? Was it safe? What did you see? (Subtext: tell me about the machetes.) I was probably like that myself before I went there.

On the night of 6 April 1994, persons unknown shot down Rwandan president Juvenal Habyarimana's plane. He was a Hutu. His killing was the catalyst of a civil war, as furious Hutu extremists in the military and police force took control of the government and sent death squads into the streets. State radio branded the minority Tutsi as the enemy and urged loyal Hutu citizens, the majority, to do their duty and defend the country against this "enemy within". In effect, to kill them all.

The outside world knew what was happening and chose to do nothing as Rwanda turned into a living hell. Almost a million people were hunted down and slaughtered in three months.

What happened at the ETO is sometimes referred to as Rwanda's Srebrenica.

For five days, the sprawling campus in a suburb of Kigali became a sanctuary of sorts for about 2,500 Rwandans, mostly Tutsis but also some moderate Hutu and Western expatriates. They came to escape the lawlessness and violence that was everywhere, and for protection from the Belgian United Nations troops billeted there. The school quickly became surrounded by squads of the murderous Interahamwe.

What happened next was as shameful as it was symbolic. French troops arrived to evacuate only white expatriates. No Rwandans, no exceptions. Immediately after this was accomplished, the UN contingent abandoned the compound, leaving the terrified men, women and children to a certain death. Most were killed within hours of the UN leaving.

I initially went to Rwanda in 2004 to see if it was feasible to make this film there. I don't know what I expected to find, but whatever I expected, it wasn't what I got.

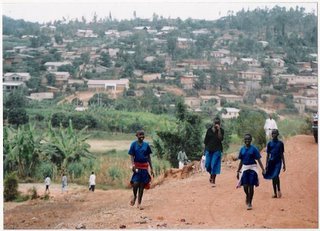

Physically, the Land of a Thousand Hills is a quite beautiful country, lush verdant green during the rainy season and parched dusty red when dry. It isn't what I would imagine a typically African landscape. No wild, wide plains full of animals here, just hills. Many of those thousand hills are terraced, planted with crops, cultivated and tended. It was testimony, both to overpopulation and extreme poverty, that it looked so agricultural, more Tuscany than The Lion King. It did, however, explain the ubiquitousness of the machete.

In Kigali, the boisterous capital, * * developed and undeveloped world co-exist. I could get a broadband connection in the hotel but would sit in darkness on my balcony and watch as the daily power cuts blacked out hillsides all around.

The Rwandese like to dress smartly and many people carry mobile phones, but many more are in bare feet and ragged T-shirts, carrying yellow plastic containers to get water from communal taps because they have none at home.

They like their football and are very clued-up about the English football leagues and their players. I often spotted obscure club shirts on children in the streets ("Oh Irony, Thy Name Is Sheffield United. Nickname: The Blades!"). The shirts were all in the fashions of a few years ago because they had arrived by way of aid packages, the discards of a more affluent world elsewhere.

All in all, though, my initial impression was of a functioning country, vibrant and peaceful and, apart from the parliament building, still pock-marked by shells, showing few physical signs of the war.

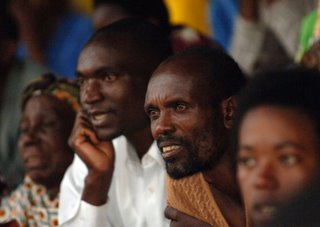

It's when you begin talking to people that you realise the scars are all psychological. They are hidden, but they're everywhere. Once you understand that, you encounter the all-encompassing horror of genocide. It's estimated that 94 per cent of the entire population witnessed some kind of extreme violence during the genocide.

The Rwandans are a reserved people, not given much to histrionic outward displays of emotion. People continually used "the war" as a reference point in their conversation: "before the war" "during the war" and "after the war". It was as if by placing their experiences into one

of those three phrases the whole emotional geography of their situation could be instantly understood. Life was innocent, or it was terrifying, or it was grief stricken. There was nothing more to say because everyone understood.

Realising that many of the shy smiles on display were a mask, to disguise some unutterable private devastation they were bound to carry around for ever, only increased this sense of melancholy and sadness.

Talking to survivors (and almost the entire country is a survivor) there was often a complete lack of emotion in their stories, just an unaffected retelling - the unimaginable terror and suffering, the horrific loss, the emptiness and guilt of their survival all told in an open, unsensational way. I would often be asked: "Why did no one do anything to help? Did no one care?" Of course I had no answer except: "We didn't know," which sounded marginally less offensive than: "We didn't care." They then say: "You must tell the world what happened here, this must never happen again." The simplicity of expression and the lack of manipulation had a deep effect on me. It became a key to how this story should be told. Just tell it. Honestly.

I knew there was no film-making infrastructure in Rwanda and that it could quite possibly be a very miserable experience all round - but, for fuck's sake, it was their story. How could it not be made there? I decided that, however difficult, we had to film in Rwanda; we had to shoot at the ETO. And we had to make the film with survivors of the genocide. They had to be allowed to tell their story.

Now, I sincerely believe that the real films about what happened in Rwanda will only be made when the Rwandans can make them for and about themselves, but at the moment, that ability didn't exist. In the meantime, though, Shooting Dogs could partially redress the persistent Western ignorance on the subject.

A film creates a sizeable financial knock-on effect anywhere it's made, injecting money that normally wouldn't be there into the local economy. Naturally, in a country as poor as Rwanda, this created a frenzied desire for jobs. A day's work as an extra paid US$16 (about £9), a vast sum, and there were often huge crowds every dawn as people looked for employment. We couldn't hire them all, of course, but, more worryingly, it was also likely that we'd be hiring people who had taken a part in the killings in 1994. I may not know who they were, but others certainly would and this could cause any degree of tension.

For all practical purposes a film set is not a democracy; at best, it's a benign dictatorship. To that end, I made a policy decision early on that there would be no differentiation among employees by way of race, nationality, ethnicity or gender.

The experienced would train the inexperienced; the local would look after the foreigner; Rwandese, German, Belgian, Ugandan, European, Tutsi, Hutu, even the English, were all just crew members. We weren't being saintly, just practical; we had to integrate people into one unit for the duration. Of course it would be naive to think this solved every difference, but not wanting to lose the financial benefits of working on the film helped to keep any resentments at a distance.

Words take on a different meaning to the people who've actually lived them. Imagine that you're terrified. Imagine that you think you are going to be killed. Imagine you are watching your mother being macheted. Imagine saying goodbye to your children before they die. Imagine watching UN soldiers save the dogs of white people but refuse to help Rwandese. Most of my cast and crew endured all this and tragically much more. Yet still they thought it important to recreate these scenes as faithfully and accurately as possible, so that we could "tell the world what happened there".

I spent more than five months there; it was some of the most exhilarating, exasperating, humbling, life-affirming time I have spent on the planet.

One night I was sitting around with an elderly Rwandan. We were sipping cold Mutzig beer and eating spicy goat brochette. He was educated and multilingual - and he had lost a child and a limb in what he called "the war". He spoke without rancour, but his voice dropped and he became barely audible as he recalled what happened to him at the Ecole Technique Officielle.

I asked him how he felt about the West or the United Nations now. He said he had been angry, very angry, for a long time, but that he had eventually reached a realisation. He quoted George Orwell's Animal Farm: "All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others. I think that Rwandans were the wrong animals."

Recently, at a screening for Shooting Dogs in a plush London theatre, I was asked a question by a rather smug film-industry type: why make another film with white men in Africa? Wasn't it really just more exploitation?

Poor old fucking Africa.

Black first, human second.

Hair-splitting like that was why no one did anything about the genocide in the first place. Of course, his was a notion born of a privileged ignorance, a politically correct nicety so hollow and irrelevant to the Rwandan reality that I cringed for them in absentia.

I wanted to tell him that he had missed the point. Spectacularly so. I wanted to tell him about the survivors' stories I'd heard, about the gut-wrenching wailing of the traumatised schoolgirls, about how Rwandans just happened to be the "wrong animals". But I couldn't. In the end I could only say: "Because the Rwandans already know what happened. You don't."

-Michael Caton-Jones

Marie (Clare Hope-Ashitey)

Marie (Clare Hope-Ashitey)